During the Roaring '20s, Atlanta, Georgia, was home to a thriving community of blues guitarists whose styles were as distinctive as their counterparts' in Mississippi, Memphis, and Chicago. Peg Leg Howell and His Gang specialized in countrified juke music. The more uptown Barbecue Bob/Curley Weaver school of players favored open-tuned 12-string guitars played with driving bass patterns and trebly slides.

Their associate Eugene "Buddy" Moss, who came to brief prominence in the 1930s, drew from their sound and what he'd learned from records. Blind Willie McTell, truly in a class of his own, blended ragtime and country blues, emerging as one of the greatest bluesmen of any era.

"Peg Leg" Howell, pictured in the early 1960s, started out as a street musician in the Decatur Street district in Atlanta. In the 1920s he recorded many songs for Columbia Records, and thus was one of the earliest musicians to record the Atlanta blues style.

The first among them to record was “Peg Leg” Howell, who performed for a Columbia Records field unit visiting Atlanta in November 1926. Born Joshua Barnes Howell in Eatonton, Georgia, in 1888, Howell was older than most of the early Atlanta bluesmen, and his repertoire extended to country reels, white mountain music, field hollers, ballads, and other preblues styles. He moved to Atlanta around 1923 after losing his leg to a shotgun blast and played with guitarist Henry Williams and violinist Eddie Anthony.

Howell, who accompanied himself on six-string guitar, was a decent and occasionally adventurous fingerpicker with a nice, steady roll and a knack for playing extended bass runs reminiscent of Blind Lemon Jefferson. His first 78, "New Prison Blues," sold well enough that Howell was back five months later with Williams and Anthony, recording as “Peg Leg” Howell and His Gang. With bracing guitar, mournful vocals, and limber fiddle lines, these exuberant 78s were among Howell's best records. His sales, though, were soon supplanted by those of Barbecue Bob, and he made his final prewar records in 1929. He resurrected his career 34 years later, recorded an album for Testament, and passed away in 1966.

The Hip Crowd

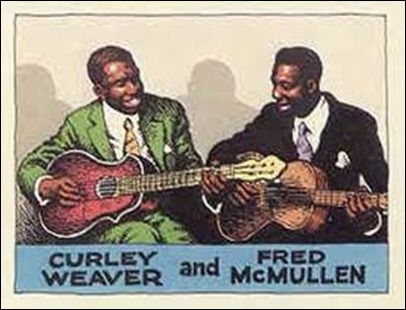

Whereas “Peg Leg” Howell sounded old-timey and countrified, Barbecue Bob (Robert Hicks), Laughing Charley Lincoln (Charley Hicks), and Curley Weaver had a decidedly hipper approach. All three favored open-tuned 12-string guitars played with zesty bass runs and highly rhythmic bottleneck. The three had grown up together in the cotton-field country around Walnut Grove, Georgia, and it's likely that Weaver's mother, Savannah "Dip" Shepard, tutored them on guitar.

By 1918, the Hicks brothers were performing at fish fries and country balls, playing songs like "John Henry" and "Po' Boy." Witnesses recalled that Robert was the better guitarist, while Charley had a stronger voice. Around 1923 Charley moved to Atlanta, found work, and acquired a 12-string guitar. His younger brother joined him there the following year and soon had a 12-string as well.

Weaver, several years younger than the Hicks brothers, moved to Atlanta around 1925 with Eddie Mapp, a talented young harmonica player. With his easy-going personality and knack for accompanying others, Weaver became a favorite among local musicians. As Buddy Moss told Blues Unlimited, "I think people liked Curley best [of the Atlanta musicians]. Curley was a guy, he could really raise behind you and he could take up the slack. You didn't have to wait for him." Moss, born in 1914, grew up in Augusta, Georgia. A harmonica prodigy who could wail like Eddie Mapp, he took up guitar after befriending Robert and Charley Hicks soon after arriving in Atlanta in 1928.

Robert Hicks launched his recording career in March 1927 after being spotted by a Columbia talent scout. Columbia identified him as Barbecue Bob on all but two of his more than 50 78s. His first release, "Barbecue Blues," sold well enough that Columbia arranged to record him in their main studio in New York City three months later. Barbecue Bob hit pay dirt with a topical blues he'd written on the train to New York, "Mississippi Heavy Water Blues," about recent catastrophic flooding in the Mississippi Delta. The record was snapped up by southern blacks, and Hicks was soon Columbia's best-selling bluesman. For the next three years, he made records every time Columbia visited Atlanta.

Barbecue Bob's 12-string playing had plenty of pizzazz, with its thumbed bass parts and speedy slide, which he apparently played with a ring. He favored one- or two-chord song structures and was equally adept at fast, clean, highly rhythmic playing and slow blues. For added effect, he'd occasionally snap the lower strings, howl and growl, or launch into solos at unexpected times. He usually tuned to open G and would sometimes capo up four frets to play in B. His original titles displayed streetwise confidence, wry humor, and a familiarity with popular blues and vaudeville themes.

On Barbecue Bob's recommendation, Charley Hicks made his first recordings for Columbia in November 1927. He proved to be a less facile guitarist than his younger brother, relying on old-fashioned frailing techniques and rarely using slide. His pseudonym, Laughing Charley Lincoln (also spelled Charlie on some releases), was reinforced by the infectious laughter heard on several of his records. Columbia teamed Laughing Charley with Barbecue Bob on his first release, "It Won't Be Long Now." Laughing Charley soon had a hit record of his own with "Hard Luck Blues." Unlike his ebullient brother, though, Laughing Charley tended to sound melancholy, and his 78s weren't as plentiful and didn't sell as well.

Barbecue Bob went on the road in the late '20s, playing with an old-time medicine show that toured from Georgia to Mississippi. He was in fine form at his final sessions, held at Atlanta's Campbell Hotel in December 1930. After recording six new solo blues, he teamed with Weaver and Moss as the Georgia Cotton Pickers. Weaver slid magnificently through their rollicking tunes, while Hicks played rhythm and Moss, just 16 and recording for the first time, wailed on harmonica.

Infectious hokum, their "Diddle-Da-Diddle" nodded to Blind Blake's popular "Diddy Wah Diddy," while "She's Coming Back Some Cold Rainy Day" borrowed melodically from the Mississippi Sheiks' "Sittin' on Top of the World." Played with unabashed heart, the Georgia Cotton Pickers sides are among the best of the pre-war juke band recordings. Tragically, Barbecue Bob Hicks died of pneumonia in 1931, and his brother Charley became a mean and dangerous drunk and never recorded again. Following a series of scrapes with the law, he murdered a man in 1955 and was sentenced to 20 years. He died in prison in September 1963.

Buddy Moss had trouble with the law as well. Learning guitar from the Hicks brothers and Weaver and absorbing influences from records by Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and especially Blind Blake, he developed a superb fingerpicking style reminiscent of Blake's. By the mid-1930s he was recording extensively for the ARC company in New York City, as a solo artist and with Fred McMullen, Weaver, Blind Willie McTell, Josh White, and others. By 1935 he was poised to become the Southeast's most important bluesman, but then the 22-year-old Moss was convicted of murdering his wife and sentenced to six years in prison. He tried to resurrect his career in 1940 with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, playing as well as he had a half dozen years earlier, but Moss never regained the momentum he'd had in the '30s. "Rediscovered" during the '60s folk-blues revival, he recorded again and worked the blues festival circuit during the '70s, but he remained a guarded, embittered man until his death in 1984.

Curley Weaver fared better than his pals. Barbecue Bob had arranged for him to record his first sides for Columbia in October 1928. Played without a slide, his first recording, "Sweet Petunia," resembled the work of the enormously popular white country star Jimmie Rodgers. Its flip side, "No No Blues," was pure Weaver, with its effective falsettos, driving 12-string strums (played in open G capoed up a couple of frets), and highly distinctive slide work.

As his slide reached its note, Weaver gave it a short, rapid shake to create a propulsive, wavering sound. Only a few other '20s blues guitarists played slide this way on records, and by the mid-'30s this sound had pretty much vanished from the blues. But Weaver was far more than a one-lick wonder: He could also bottleneck with dead-on intonation worthy of Tampa Red, as heard on his 1931 duets with Clarence Moore.

Weaver really hit his stride during the mid-'30s, playing exceptional slide at his 1933 ARC sessions with Moss, McMullen, and Atlanta singer Ruth Willis. His falsetto-laced "Tippin' Tom" and "Birmingham Gambler" revisited the idiosyncratic style of "No No Blues." He teamed with McMullen and Moss as the Georgia Browns, a trio modeled after the Georgia Cotton Pickers. Like their predecessors, on which Weaver had also played, these records are fabulous samples of string band juke music. The good-time "Tampa Strut" displays the guitarists' unstoppable rhythmic feel and wall-to-wall bottleneck, as well as Moss' mournful harmonica solos. "Next Door Man" featured Weaver in standard tuning while McMullen played bottleneck in open G.

Blind Willie McTell

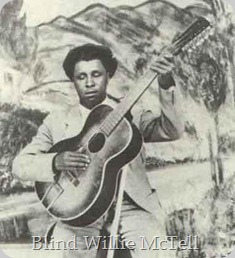

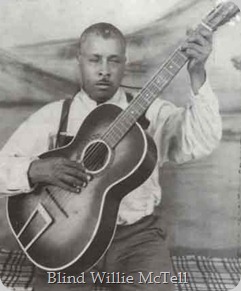

Among the plethora of Atlanta's blues guitar stars, none shone brighter than Blind Willie McTell, who had it all—a shrewd mind, insightful lyrics, astounding nimbleness on a 12-string guitar, and a sweet, plangent, instantly recognizable voice. He was sensitive, confident, and hip-talking, a beloved figure in the various communities in which he moved, and he played sublimely, a result of both natural talent and constant playing. McTell's records reveal a phenomenal repertoire of blues, ragtime, hillbilly, spirituals, ballads, show tunes, and original songs. They seldom sound high-strung or harrowed, projecting instead an exuberant personality and indomitable spirit.

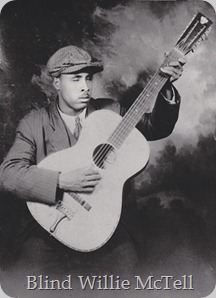

Willie Samuel McTell was born circa 1898 near Thomson, Georgia. He started performing as a teenager and had acquired his first 12-string guitar, probably a Stella, by 1927. At first he used a bottleneck for slide and later switched to a metal ring or thimble. He favored standard and open-G tunings, and many of his songs had a pronounced ragtime influence.

McTell inaugurated his recording career in October 1927, cutting two 78s during the Victor label's field trip to Atlanta. After a pair of slideless blues, McTell recorded the first of many slide masterpieces, "Mama, T'Aint Long Fo' Day," working his bass and treble strings in a manner that had more in common with Texas gospel great Blind Willie Johnson than the Atlanta bluesmen. McTell signed a contract with Victor and a year later recorded two more 78s, including his best-known composition "Statesboro Blues". While this song is revered today as Duane Allman's signature bottleneck song with the Allman Brothers Band, the McTell version is slideless.

All of McTell's initial Victor 78s were hardcore blues. In October 1929, he moonlighted for the first time with Columbia Records, which would release many of his more adventurous sides. McTell was in extraordinary form at his debut Columbia session, recording the classics "Atlanta Strut" and "Travelin' Blues." In "Atlanta Strut" he sang of meeting up with a "gang of stags" and a little girl who looked "like a lump of Lord have mercy," while his booming 12-string imitated a bass viol, cackling hen, crowing rooster, piano, slide guitar, even a man walking up the stairs! He fingerpicked "Travelin' Blues" with extraordinary finesse, using his slide to mimic a train's engine, bell, and whistle, and then did a note-perfect chorus of "Poor Boy." Columbia identified him on records as Blind Sammie, but for anyone who'd heard the Victor 78s, there was no mistaking who this artist was. Issued in early 1930, "Travelin' Blues" sold more than 4,200 copies, but with the onset of the Depression, blues record sales soon plummeted. When "Atlanta Blues" came out in May 1932, only 400 copies were pressed.

Curley Weaver, who'd become fast friends with McTell around 1930, accompanied him in the studio for the first time at a 1931 Columbia session. McTell, now moonlighting as Georgia Bill, played unsurpassed ragtime-influenced 12-string on his unaccompanied "Georgia Rag," while the 78's flip side, "Low Rider's Blues," featured Weaver's light-touched bottleneck solo, with McTell shouting encouragement. The duo also backed Ruth Willis on a pair of tracks. McTell's unaccompanied "Southern Can Is Mine"/"Broke Down Engine," a gem of a performance, sold only 500 copies. McTell's sole session of 1932 coupled him with another female singer, Ruby Glaze, and renamed him Hot Shot Willie. Their 78 of "Lonesome Day Blues" sold only 124 copies and is among his rarest records today.

Despite discouraging sales, McTell's luck at scoring recording sessions held. In September 1933 he accompanied Weaver and Moss to New York City for the marathon ARC session that, in hindsight, was the swan song of the early Atlanta blues guitar scene. McTell played second guitar on records credited to Weaver and Moss, who in turn backed McTell on two dozen gospel and blues selections. These records are among the best prewar blues guitar collaborations. McTell and Moss both recorded two versions of "Broke Down Engine" and covered Bumble Bee Slim's "B and O Blues" at the session, with Weaver accompanying each of them. Moss remembered that McTell acted as their leader in New York, both at the session and in navigating the subways.

While McTell kept a home base in Atlanta during the 1930s, he was an inveterate rambler. During summers, he played for vacationers in Miami and the Georgia Sea Islands. When the tobacco crop came in during July and August, he'd head to warehouses and hotels around Statesboro, Winston-Salem, and Durham, North Carolina. He refused car rides from strangers and typically journeyed by train and bus, confident in his ability to support himself by playing for tips in stations and depots, small clubs, churches, and on the streets. He acted as his own manager and agent, often arranging bookings by telephone.

In 1934 McTell married Ruthy Kate Williams, a student he'd heard singing at a high school ceremony in Augusta. On occasion she sang spirituals with McTell and danced onstage while he played matinees at the 81 Theater, sometimes with Weaver sitting in. After seeing one such performance there in 1935, recording executive Mayo Williams invited the McTells and Weaver to Chicago to record for Decca.

At these Chicago sessions, the McTells performed several old-time gospel slide tunes reminiscent of Blind Willie Johnson, with whom he'd toured a few years earlier. Weaver joined McTell on "Bell Street Blues" and several other secular tunes, finessing quick-fingered solos behind McTell's 12-string bass and rhythm. McTell backed Weaver on several blues as well, playing with such wonderful subtlety on "Tricks Ain't Walking No More" that his 12-string almost sounds like a six-string. McTell was paid $100 per side—excellent pay during the Depression—although few of these records were issued. None of the records made at his next session, held by Vocalion in Augusta in July 1936 with Piano Red, were issued or even survive today.

In November 1940, folklorist John Lomax and his wife found McTell wailing away at the Pig 'n' Whistle (a drive-in rib joint) and brought him to their hotel to record for the Library of Congress' Archive of American Folk Song. (On the drive to the hotel, the story goes, McTell called out directions and pointed to landmarks as if he could see them.) The non-commercial session yielded a breathtaking array of folk ballads and spirituals, as well as a blues, a rag, a pop song, and insightful monologues on old songs, blues history, and life itself. McTell laced "Dying Crapshooter's Blues," one of his most ambitious and picturesque compositions, with hip gambling images and an unforgettable melody. His lonesome slide during the spirituals "I Got to Cross the River Jordan," "Old Time Religion," and "Amazing Grace" resembled Blind Willie Johnson's old 78s, although unlike Johnson, who played in open D, McTell played his in open G capoed up two frets. In less than an hour, McTell gave Lomax some of the finest records he'd ever make.

While amplified jump blues became the dominant sound on jukeboxes and blues radio broadcasts just after World War II, by the late 1940s the stripped-down sound of John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and Lightning Hopkins was attracting an audience. In May 1949, an executive from New Jersey–based Regal Records advertised on Atlanta's black radio for country blues guitarists, and McTell and Weaver answered the call, cutting 20 blues and gospel selections. These excellent-sounding records reveal a wealth of innovative bass lines and chords, masterfully fingerpicked solos, and sublime slide. Their excited "You Can't Get That Stuff No More" revisited a 1932 Tampa Red hit, while McTell's remakes of "Love Changin' Blues" and "Savannah Women" featured sweet and low-down slide. Only three of the McTell singles were issued by Regal, however, two of them religious. On the sole blues release, McTell was identified as Pig 'n' Whistle Red.

Several months later, Weaver, 43, recorded two solo singles on acoustic guitar for the Sittin' In With label, including a spirited remake of "Tricks Ain't Walkin' No More," which he'd recorded for Decca a dozen years earlier. These were Weaver's last recordings. He formed a trio with Buddy Moss and Johnnie Guthrie, playing around Georgia in the early '50s, and retired from music when his eyesight failed later in the decade. He died in 1962 and was buried in a rural churchyard in Almon, Georgia, where "Tricks Ain't Walking No More" is etched beneath his name on the tombstone.

McTell's next sessions took place during autumn 1949. Ahmet Ertegun saw him playing on a street corner and convinced him to record for his fledgling Atlantic Records. "I had collected many recordings he had made for RCA Victor, and I thought I recognized his voice, but I wasn't sure," Ertegun explained to filmmaker David Fulmer in 1992. "I asked him his name and discovered he was the famous Blind Willie McTell. He spoke of having no interest in recording anything except religious music and would only play the blues if I would release it under another name. Therefore, we decided on the pseudonym Barrelhouse Sammy. He was a charming, ebullient, but soft-mannered person." For the Atlantic sessions, McTell reprised songs he'd recorded for Lomax—"Kill It Kid," "Delia," "Dying Crapshooter's Blues"—as well as blues, a rag, and several spirituals played slide-style in the vein of Blind Willie Johnson. With its thunderous bass runs and behind-the-bridge strums, McTell's cover of "Pinetop's Boogie Woogie" bordered on prescient rock 'n' roll. On subsequent listening to the acetates, Atlantic executives apparently deemed McTell's solitary blues a thing of the past, and his sole Atlantic single, "Kill It Kid" backed with "Broke Down Engine Blues," came out credited to Barrelhouse Sammy (The Country Boy).

During the '50s McTell frequented the Blue Lantern Club, performing tableside as well as in the parking lot of the all-white restaurant. He broadcasted religious music over local radio stations and sang tenor for the glee club of the Metropolitan Atlanta Association for the Blind. In September 1956, McTell made his final recordings for Ed Rhodes, who owned a record store near the Blue Lantern. Rhodes supplied him with corn liquor, and while McTell seemed to get looser as the session progressed, he played with drive and precision. McTell performed all 18 selections without a slide, covering originals, pop songs, old blues by Blind Blake and the Hokum Boys, and hillbilly numbers such as "Wabash Cannonball." Asked about songs, he told Rhodes, "I jump 'em from other writers, but I arrange 'em my way."

Blind Willie McTell died in August 1959, and his wish to be buried with his 12-string guitar was not honored. While McTell, Curley Weaver, the Hicks brothers, Peg Leg Howell, and their prewar contemporaries created stacks of terrific blues recordings, precious little of their influence resounds in modern music.

Unlike contemporaries such as Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters in the Mississippi Delta and Tampa Red in Chicago, their sound did not become a cornerstone of postwar blues and rock 'n' roll, but rather a glimpse back to a bygone era. Fortunately, virtually everything they recorded is now available on CD, and it's just as remarkable and exhilarating as when it was first recorded.

Excerpted from Acoustic Guitar magazine, October 2002, No. 118.

Excerpted from Acoustic Guitar magazine, October 2002, No. 118.

I hope that you are enjoying learning about these blues greats as much as I am! These amazing musicians really lived their music, and I find their stories fascinating. Thanks so much for reading!

Until Next time ~

Musician By Night . . .

No comments:

Post a Comment